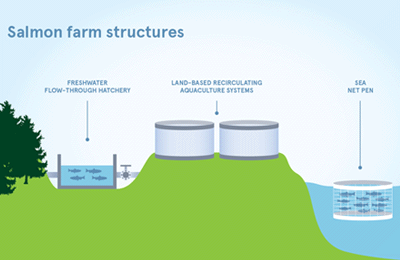

Figure 1: Salmon farm structures in current use ©Fidra

Concerns about the impact[1] of salmon farms on our lochs and seas are increasing, especially with regulations relaxed due to Covid-19. Alongside this is ambition from the Scottish Government and salmon producers to grow the industry. Is closed containment the answer to sustainable growth, with salmon pens built inside specialist facilities?

Why we are asking the question

Scottish salmon is currently produced in open net pens in the seas and lochs of west and north Scotland.

The Scottish Environmental Protection Agency, SEPA, regulates the amount of salmon (biomass) a farm can hold and the medicines they use. As restrictions associated with Covid-19 have led SEPA to relax these regulations[2], it seems timely to review alternatives to open net pens. Relaxed regulations will allow increased medicinal use[3] and biomass[4], meaning more waste, chemical treatments and feed can go into the marine environment from open net pens. While understandable under the present conditions, alternative technologies such as closed containment could remove the need for such regulations to be relaxed in times of crisis. Their use would certainly result in reduced impacts on the marine environment.

Canada report focuses on four production systems

Canada’s much publicised promise[5] to review its salmon farming by 2025 led to production of the ‘State of Salmon Aquaculture Technologies’ report[6]. The report focus is on four alternative technologies to conventional open net pens :

- Land-based recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS)

- Hybrid technology involving land and marine based systems

- Floating closed-containment systems (CCS)

- Offshore open production systems.

All four systems show improvements over open net pens, which currently account for about 98% of global salmon production. Each system has different advantages and disadvantages in terms of environmental, social and economic performance.

Are alternatives to open net pens ready to use?

Land-based RAS and hybrid ‘off the shelf’ systems are available and ready for commercial development. The report suggests that it would take at least another 2 years to understand whether commercial-scale land-based RAS are profitable. Hybrid systems notably still involve the use of open net pens, but for a shorter time. Floating closed containment needs 2-5 years of further development, and offshore systems 5-10 years.

Additional technologies such as sensors, artificial intelligence and remote operated vehicles can support advancements in all of these systems and should be considered in parallel.

Land-based recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS)

Some systems have produced up to 1000 metric tons (mt) of salmon annually. Those being constructed now tend to be 3000mt or more. High capital costs means larger facilities will gain efficiencies of scale and achieve better financial returns.

Hybrid systems with land-based and marine sites

In the increasingly used hybrid approach, land-based RAS produce ‘post-smolts’ weighing 250g – 1kg, which are transferred to marine open net pens to ‘grow-out’. Less time in open net pens reduces some environmental risks at marine sites, and avoids costly land-based systems in the grow-out phase. Future grow-out could involve near-shore closed-containment or offshore technologies, but present focus is on open net pens at near-shore sites.

Figure 2: CCS Aquafarm Equipment Neptune 3. Reproduced from ‘State of Salmon Aquaculture Technology, 2019’ [6]

Floating closed-containment systems (CCS) enclose floating pens with solid or flexible walls. This enables collection of feed and faeces waste, and provides barriers to diseases, parasites, wildlife interactions, and escapes.

Most systems presently in operation grow smolts from land-based systems up to post-smolt (1-2kg) size, with further grow-out to market size (5-6kg) in open net pens. Although some are used to grow salmon to full market size, they will most likely be an intermediate step between land-based RAS and open net pens.

Offshore systems

Offshore systems operate in minimum depths of 20 meters and minimum wave heights of 1 metre, within 25 nautical miles and with reliable access to on-shore and off-shore infrastructure. Designs vary from including staff accommodation to being fully automated, and structures are mostly open although some re-purposed marine vessels offer full containment that can move.

Assessing whether the aquaculture technology is sustainable

The report assesses the four aquaculture technologies under several environmental, social and economic categories.

Seven key environmental criteria are considered: marine escapes, salmon diseases, waste effluent, chemical release, wildlife interactions, water usage and energy usage. Overall, all four production systems showed improvements over conventional net pens. Land-based RAS systems offered the most comprehensive decrease in impacts on the marine environment, with zero marine escapes, wild salmon disease impacts and wildlife interactions. Additional research is needed for floating closed-containment and offshore systems.

While all four systems also offer improvements in the three social criteria used – local, global and consumer support – the report acknowledges that support would not be universal.

Seven economic criteria of the new technologies are assessed: profitability, capital cost, operational cost, financial risk, supply chain availability, economic benefits and expansion opportunities. The report concludes that land-based RAS and hybrid systems are ready for commercial application in Canada, while the others still needed 5-10 years development.

Encouraging alternatives to open nets

The report emphasizes that national legislation and policy need to make clear requirements for aquaculture in terms of environmental and social performance, to send the appropriate signals for investors to develop the technologies that meet the challenge. To encourage innovation, a number of measures are suggested based on other countries, such as development licences with reduced fees and marine sites with biomass allocations for innovative technologies. While the report is intended to address the aquaculture industry in British Colombia, Canada, it is appropriate as a current reference for anywhere farming Atlantic salmon.

As restrictions around the global Covid-19 pandemic continue, it is unlikely that ‘normal’ practices will resume this year in the global salmon farming industry, and innovation is likely to stall. In Scotland, the current relaxation of regulations highlights issues in processes and systems, and is undoubtedly going to have a significant environmental impact. It begs the question – do we want to return to ‘normal’ longterm? The development and uptake of new technologies that have minimal effect on the marine habitat will be more important than ever.

Figure 3: Offshore systems in Norway. Reproduced from ‘State of Salmon Aquaculture Technology, 2019’ [6]

[2] https://coronavirus.sepa.org.uk/regulatory-position/finfish-aquaculture-regulatory-positions/

[3] https://coronavirus.sepa.org.uk/media/1050/sea-lice-medicine-finfish-aqua-reg-position.pdf

[4] https://coronavirus.sepa.org.uk/media/1013/covid19-finfish-aquaculture.pdf

[5] https://pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/2019/12/13/minister-fisheries-oceans-and-canadian-coast-guard-mandate-letter

[6] https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/aquaculture/publications/ssat-ets-eng.html

Tags: aquaculture, Atlantic salmon, Canada, closed containment, covid-19, RAS, recirculating aquaculture system, salmon farming, Scotland, SEPA